Internal Texturing: Hidden Surface Variation

In the world of design and manufacturing, we often celebrate the visible: the sleek curve of a smartphone, the glossy finish of a car, the flawless surface of a countertop. But beneath, within, and integral to these surfaces lies a silent, powerful force that dictates far more than aesthetics. This force is internal texturing—the deliberate, often hidden, variation within a material’s structure or on its non-visible surfaces. It is the unsung hero of functionality, the secret behind a satisfying tactile experience, and a critical engineering tool hiding in plain sight. While external texture appeals to the eye, internal texturing speaks to the hand, the ear, and the very integrity of an object.

What Exactly is Internal Texturing?

At its core, internal texturing refers to the controlled modification of a surface or subsurface that is not primarily intended for visual consumption. Unlike a decorative wood grain or a brushed metal finish, internal texture serves a mechanical, chemical, or physical purpose. It can exist on the inside of a component, on a surface that will be bonded to another, or within the layers of a material itself.

Think of it this way: external texture is the facade of a building, while internal texturing is the roughness of the concrete footing that ensures it bonds securely to the earth, or the specific profile of the steel beams that interlock. It is a functional geometry applied at a micro or macro scale. This can include patterns of microscopic peaks and valleys (like in adhesive bonding surfaces), engineered porosity (like in filters or biomedical implants), or specific subsurface structures created during processes like injection molding or 3D printing that affect the part’s final properties.

The Invisible Engine: Key Applications and Benefits

The applications of internal texturing are vast and cross-disciplinary. Its benefits are realized not in the first glance, but in the lasting performance of a product.

1. Adhesion and Bonding: This is one of the most critical roles. A perfectly smooth surface is often terrible for glue or paint. Internal texturing, such as plasma etching, chemical roughening, or laser ablation, creates a larger surface area and mechanical “anchors” for adhesives to grip. The hidden texture on the inside of a tennis racket’s frame or an automobile’s trim piece is what ensures the layers stay fused together under stress.

2. Structural Integrity and Lightweighting: In additive manufacturing (3D printing), internal texturing isn’t just about the outer shell. Infill patterns—the honeycomb, grid, or triangular structures inside a printed part—are a perfect example. They provide crucial internal support and strength while minimizing material use and weight. The specific texture of this infill directly impacts the part’s flexibility, durability, and load-bearing capacity.

3. Fluid and Air Management: Internally textured surfaces are paramount in controlling flow. In aerospace, specific textures on internal ducting can reduce drag and turbulence. In microfluidics, etched channels guide minute amounts of liquid with precision. The engineered porosity in filters or wicking materials relies entirely on controlled internal texture to trap particles or move fluids.

Tactile Experience and Human Interaction

Perhaps the most subtly powerful application is in how we feel an object. Internal texturing can be engineered to influence the tactile response of an otherwise smooth surface. A polymer panel might feel solid, soft, or cheap based on the subsurface texture created during molding, which affects how it flexes and resonates when touched.

Consider the subtle, non-slip grip zones on the inside of a camera body or a tool handle. This texture isn’t for show; it’s for secure, confident interaction. The haptic feedback in many touchscreens and trackpads is simulated through precise vibrations, but future interfaces may use actual surface deformation via subsurface actuators—a form of dynamic internal texturing. The goal is to create a sensory dialogue that feels intuitive and high-quality, building trust in the product without the user consciously knowing why.

Manufacturing Methods: Creating the Hidden Landscape

Creating these hidden textures requires specialized techniques. The method chosen depends on the material, the required precision, and the function of the texture.

Molding and Casting: The most common method. A texture is etched or machined into the mold cavity itself. When material is injected or poured, it replicates that texture on the part’s surface. This is how the soft-feel texture on plastic grips or the fine grain on interior automotive panels is made—it’s an internal texture of the mold transferred outward.

Chemical and Electrochemical Etching: These processes use controlled corrosion to remove material and create micro-scale surface variations. They are excellent for preparing metal surfaces for bonding or painting, creating uniform roughness that is invisible to the naked eye but transformative for adhesion.

Laser Texturing (Ablation/Interference): A highly precise and flexible tool. Lasers can create extremely fine and complex patterns—dots, grooves, cross-hatches—on almost any material. It’s used for creating hydrophobic surfaces, improving lubricant retention on engine parts, or marking surgical tools with textures that reduce tissue adhesion.

Additive Manufacturing: 3D printing is a playground for internal texturing. Software allows designers to specify not just the outer shape, but the exact internal lattice or infill structure, enabling properties like variable flexibility, energy absorption, or thermal management within a single, seamless part.

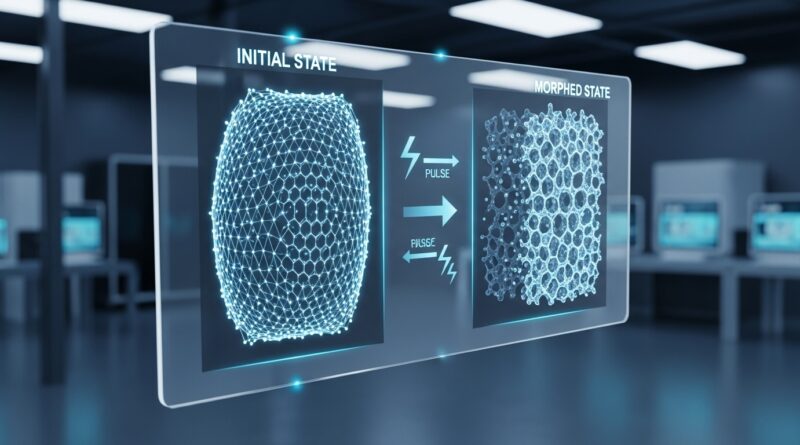

The Future: Smart Textures and Biomimicry

The frontier of internal texturing is moving towards dynamic and intelligent systems. Imagine surfaces that can change their internal texture in response to heat, electricity, or a signal—like an aircraft wing that can optimize its surface smoothness in flight. Research in metamaterials—materials engineered with internal structures that manipulate light, sound, or vibration in unnatural ways—relies entirely on precise internal texturing at a microscopic scale.

Furthermore, biomimicry continues to be a rich source of inspiration. The incredible strength of bone comes from its complex internal porous texture. The lotus leaf’s self-cleaning ability stems from a specific nano-scale surface texture. Shark skin reduces drag through microscopic riblet patterns. By reverse-engineering and applying these hidden biological textures to human-made objects, we can create materials that are stronger, more efficient, and more adaptive.

Conclusion: Looking Beneath the Surface

Internal texturing reminds us that true quality and innovation often lie beneath the surface. It is a discipline where engineering meets artistry to solve functional problems in elegant, hidden ways. From the phone in your hand to the car you drive and the medical implant that saves a life, hidden surface variations play a pivotal role.

As designers, engineers, and manufacturers, embracing the power of internal texturing means shifting our perspective. It challenges us to design not just for the eye, but for the hand, for the environment, and for the relentless forces of physics. The next time you interact with a product that feels just right, that holds together under pressure, or performs a silent miracle of function, consider the hidden landscape within. That is the powerful, unseen world of internal texturing.