Internal Surface Texture: Hidden Variation Within

Look around you. The objects you see—your phone, a coffee mug, the desk—are defined by their external surfaces. We judge them by their smoothness, their gloss, their tactile feel. But what about the surfaces we cannot see? The intricate, hidden landscapes that exist inside components are often the true arbiters of performance, efficiency, and failure. This is the realm of internal surface texture, a world of profound variation that operates in the shadows, dictating the lifeblood of systems from human arteries to jet engines.

Beyond the Naked Eye: Defining the Internal Landscape

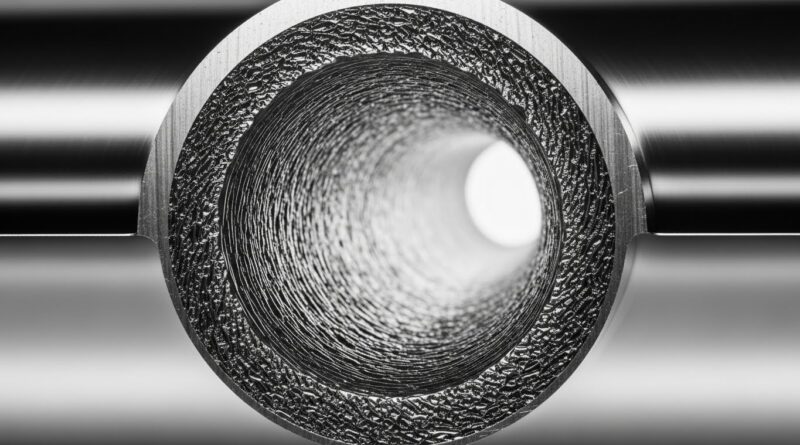

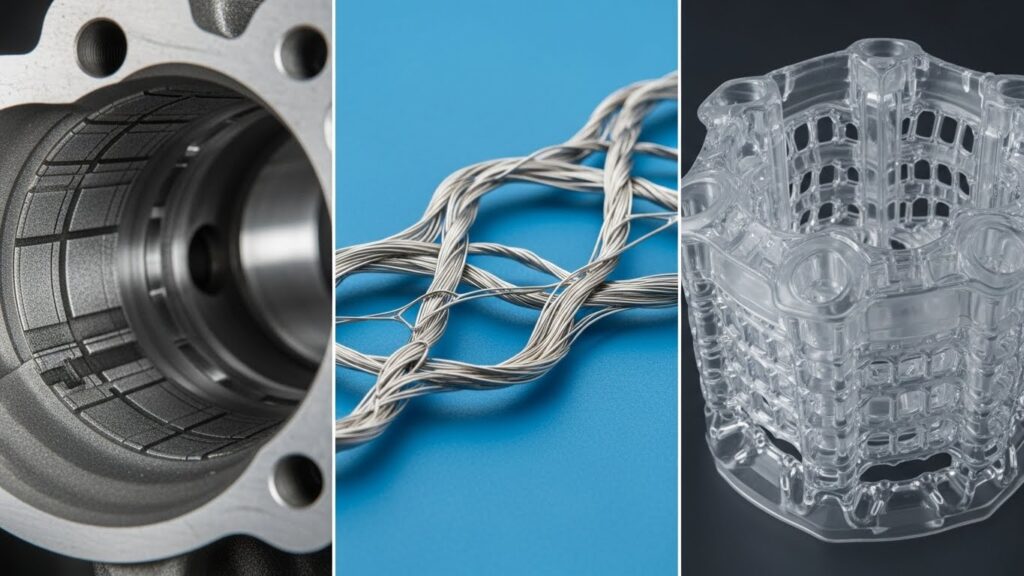

Internal surface texture refers to the microscopic deviations from a perfectly smooth, ideal surface on the inside of a component. Think of the bore of a hydraulic cylinder, the cooling channels in a turbine blade, or the lumen of a medical stent. Unlike external surfaces, these are often created by processes like drilling, honing, casting, or additive manufacturing, leaving behind a unique “fingerprint.”

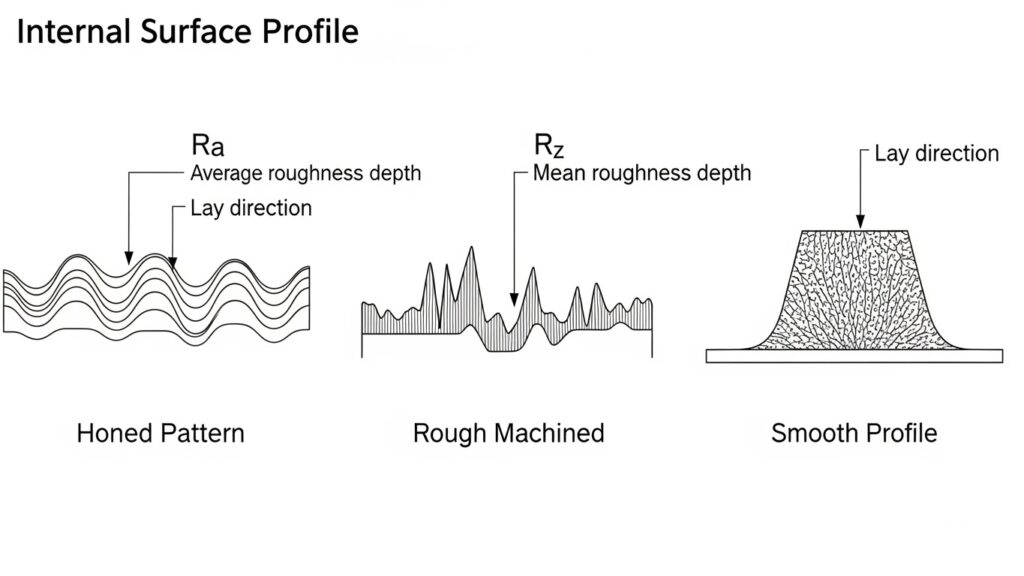

This texture is quantified by parameters like Ra (Average Roughness), Rz (Maximum Height), and Rsm (Mean Spacing). A low Ra value indicates a smoother surface, while a higher value denotes more roughness. But the numbers only tell part of the story. The character of the texture—whether it’s composed of sharp peaks, rounded valleys, directional scratches (lay), or a random pattern—is equally vital. This hidden variation is not a flaw to be universally eliminated; it is a design feature to be meticulously engineered.

The High Stakes of Hidden Roughness: Where It Matters Most

The impact of internal surface texture is felt across physics and physiology. Its influence is most pronounced in a few key areas:

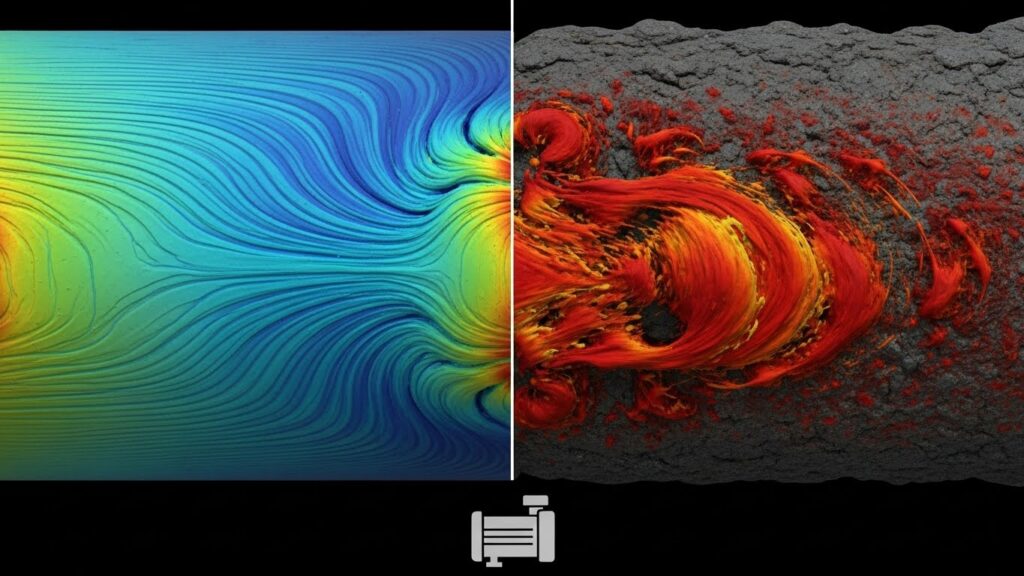

Fluid Dynamics and Flow: This is perhaps the most significant domain. In pipes, tubes, and channels, surface roughness creates friction at the boundary layer. A rougher interior increases turbulence and resistance, requiring more energy to pump fluids or gases. In fuel injectors, precisely controlled texture can promote beneficial fuel atomization. Conversely, in cardiovascular stents, an overly rough interior can disrupt blood flow and promote dangerous clotting.

Fatigue and Structural Integrity: Microscopic valleys on an internal surface act as stress concentrators. Under cyclic loading (like in an engine block or a landing gear component), cracks are most likely to initiate at these tiny imperfections. A poorly finished internal bore can become the birthplace of catastrophic failure, hidden from inspection until it’s too late.

Heat Transfer: Internal surfaces in heat exchangers, cooling jackets, and electronic thermal management systems rely on texture. A rougher surface can increase the surface area for heat exchange, potentially improving efficiency. However, if the texture traps insulating bubbles or impedes fluid flow, it can have the opposite effect. The balance is delicate and application-specific.

From Mass Production to Personalized Medicine: Applications Unveiled

The mastery of internal surface texture is transforming industries:

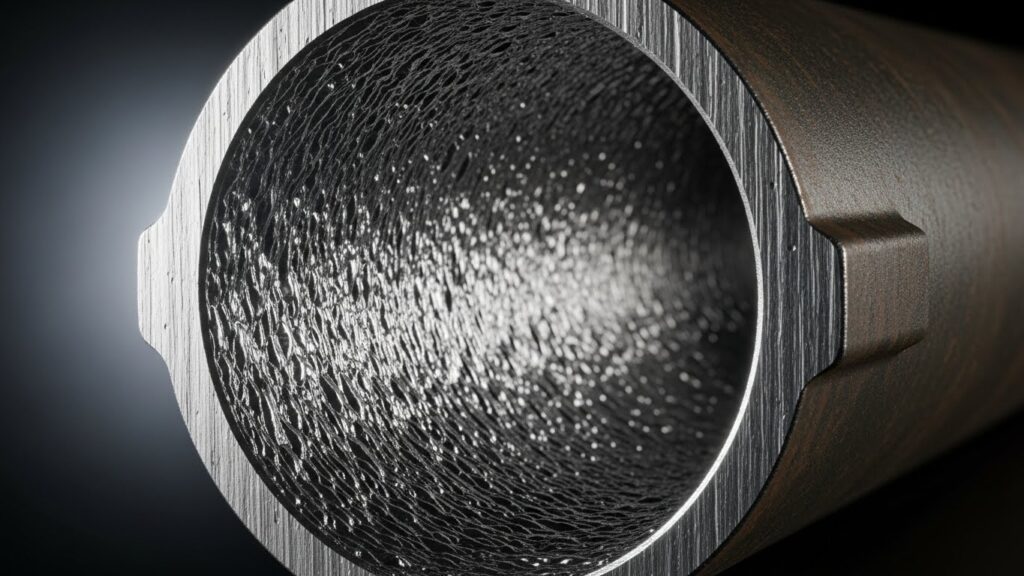

Automotive and Aerospace: Cylinder liners are honed to a specific cross-hatch pattern. The peaks hold oil for lubrication, while the valleys distribute it. This controlled roughness minimizes friction and wear, directly impacting engine life and emissions. In aerospace, the internal cooling channels of turbine blades are designed with surface textures that maximize heat dissipation, allowing engines to run hotter and more efficiently.

Medical Devices and Implants: Here, texture is a biological interface. The interior of synthetic vascular grafts is designed to be smooth to prevent thrombus formation. In contrast, the external surface of a hip implant stem is often roughened to encourage bone ingrowth—a clear example of how texture requirements diverge on a single part. Inside drug-eluting devices, texture can control the release rate of pharmaceuticals.

Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): This technology has brought internal surface texture to the forefront. Complex internal channels, impossible to machine, can now be printed. However, the “as-printed” surface of metal or polymer parts is often notoriously rough, a byproduct of the layer-by-layer process. Post-processing techniques like internal flow polishing, chemical smoothing, or micro-machining are becoming critical to functionalize these incredible internal geometries.

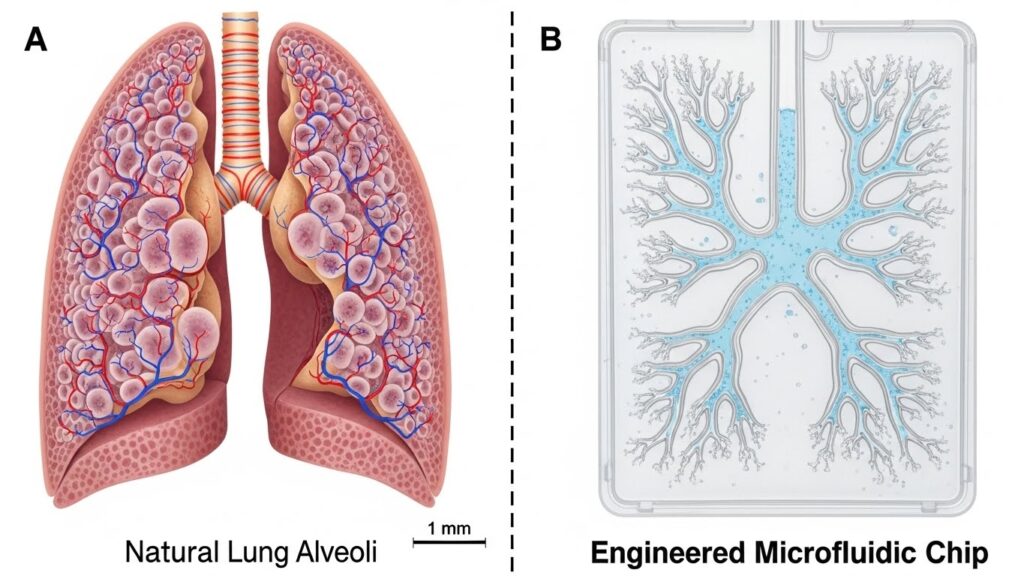

Nature’s Mastery: Biomimicry and Internal Surfaces

To truly appreciate the sophistication of internal texture, we need only look to biology. Evolution has optimized internal surfaces over millennia. Our own arteries are lined with a delicate endothelial layer that minimizes turbulent blood flow. The lungs contain alveoli with a complex, fractal-like surface area to maximize gas exchange. The xylem in plants uses precisely structured internal channels to move water against gravity with incredible efficiency.

These natural designs are a blueprint for innovation. Researchers are studying the low-drag skin of sharks, not just externally, but the internal structures that support it. The goal is to biomimic these textures to create next-generation coatings for ship hulls or even the interior of pipelines, reducing drag and energy consumption on a global scale.

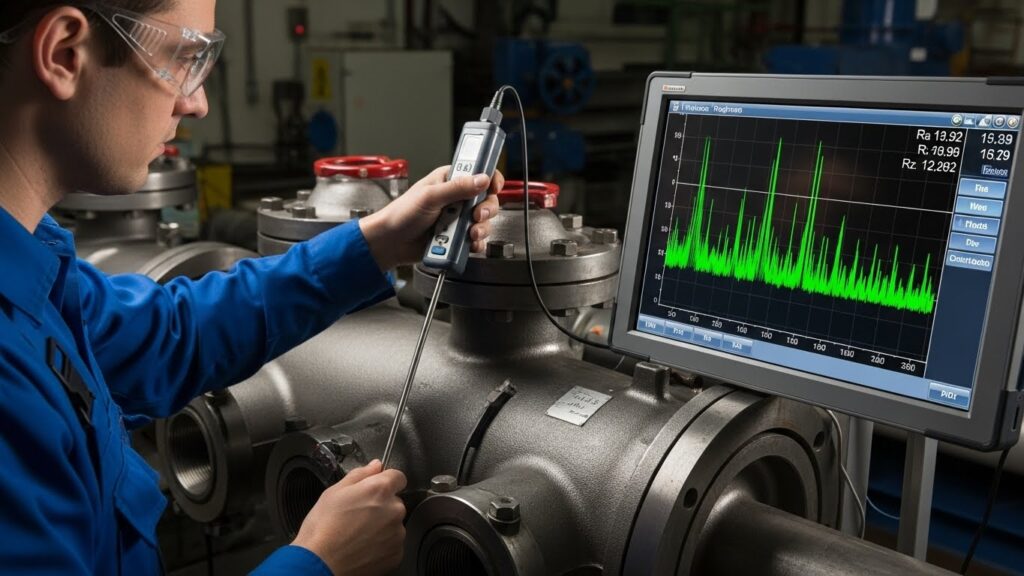

Measuring the Immeasurable: The Challenge of Inspection

A major hurdle with internal surface texture is measurement. You can’t run a standard contact profilometer inside a long, narrow bore. This has driven innovation in metrology. Non-contact methods are essential:

Air Gauging: Uses airflow between a probe and the surface; changes in flow or backpressure correlate to roughness.

Internal Profilometers: Specialized stylus instruments on long, flexible arms that can travel into cavities.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Endoscopy: Using light to create high-resolution 3D maps of internal surfaces, crucial in medical and delicate component inspection.

This “inspection challenge” is why internal texture is sometimes a controlled process outcome rather than a 100% inspected feature. If the manufacturing process (e.g., honing, grinding, etching) is stable and validated, the resulting texture is assumed to be within specification.

Embracing the Variation: A Call for Conscious Design

The conclusion is clear: internal surface texture cannot be an afterthought. It must be a conscious, specified, and validated element of the design process. Engineers must move beyond simply calling out a generic Ra value on a drawing. They must consider the functional need: Is it for lubrication, adhesion, flow efficiency, or biocompatibility?

The future lies in functional surface engineering—designing and creating specific internal textures for specific purposes. As manufacturing technologies like nanofabrication and precision additive manufacturing advance, our ability to craft these hidden landscapes will become a primary driver of innovation, from creating more efficient heat sinks for quantum computers to engineering artificial organs with perfectly tuned internal vasculature.

The hidden variation within is no longer just a manufacturing artifact. It is a frontier of design. By shedding light on these unseen surfaces, we unlock performance, longevity, and capabilities that smooth, idealized models could never predict. The true texture of progress, it turns out, lies beneath the surface.