Beveled Ends: Angled Tips for Movement

Look around. The world is not made of perfect right angles and blunt, abrupt stops. From the gentle slope of a wheelchair ramp to the aerodynamic curve of a high-speed train, movement is often facilitated by an angle. This is the domain of the beveled end—a seemingly simple design choice with profound implications for function, safety, and aesthetics. More than just a chamfered edge, a beveled end is a directive for motion, a subtle guide that tells people, objects, and even energy where to go and how to get there smoothly.

The Philosophy of the Angle: Why Beats Blunt

At its core, a beveled end solves a problem of transition. A blunt end creates a hard stop, a perpendicular barrier that must be overcome with force or effort. It’s a wall. A bevel, however, replaces a wall with a bridge. By introducing an angled plane, it reduces the effective height of an obstacle, distributes force across a wider area, and creates a gradual pathway from one state to another.

Think of a sled. A flat-fronted sled hitting a snowbank stops dead. A sled with a curved, angled front—a natural bevel—rides up and over, converting forward momentum into upward lift. This principle is universal. In ergonomics, a beveled desk edge prevents painful contact pressure on your wrists. In plumbing, a beveled pipe end ensures a better seal and easier alignment. The angle invites interaction rather than resisting it. It’s the difference between a “no” and a “please, proceed.”

Guiding Human Movement: Architecture and Urban Design

Nowhere is the power of the beveled end more tangible than in the spaces we inhabit. Urban planners and architects have long used angled transitions to orchestrate the flow of human traffic and enhance accessibility.

Consider the humble curb ramp, or “dropped curb.” The beveled end of the sidewalk is a civil rights victory in concrete, enabling wheelchair users, parents with strollers, and travelers with suitcases to navigate the city. It’s a deliberate design for inclusive movement. Similarly, the flared ends of staircases or the angled kick plates at the base of doors subtly guide foot traffic and protect surfaces from damage. In grander terms, the sloping entrances of modern museums or the ramped approaches to ancient temples use beveled forms on a monumental scale to create a sense of procession and arrival, building anticipation as one moves from the outside world into a sacred or contemplative space.

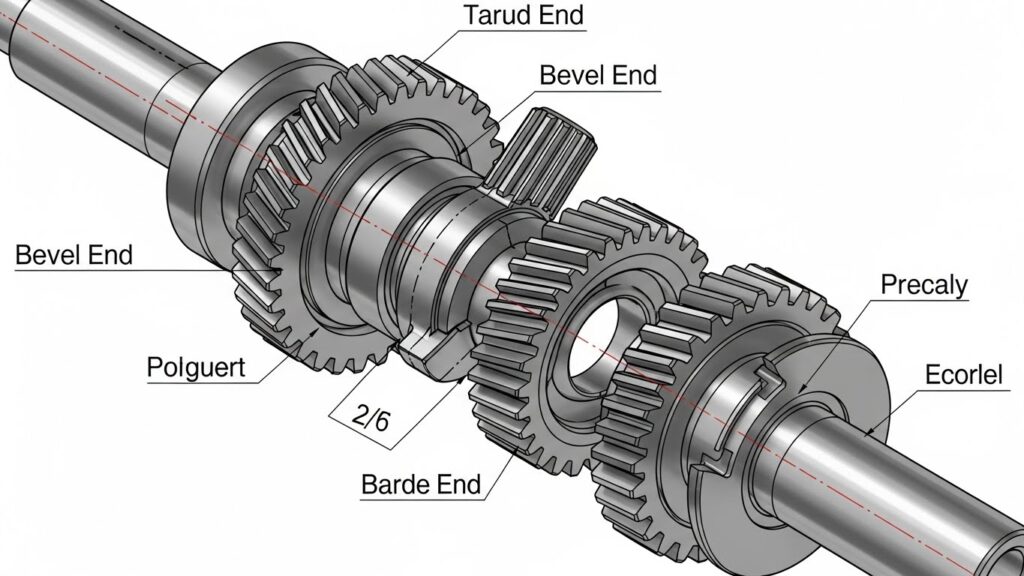

Facilitating Mechanical Motion: Engineering and Manufacturing

In the mechanical realm, beveled ends are non-negotiable for efficiency and assembly. They are the workhorses of seamless operation. A pipe or shaft with a beveled end, for instance, aligns more easily with its coupling. The angle acts as a funnel, compensating for minor misalignments and allowing parts to slide into place—a principle critical in everything from automotive engines to complex hydraulic systems.

This “lead-in” function is paramount. Without a bevel, threading a bolt or inserting a precision shaft becomes a frustrating game of millimeter-perfect accuracy. With a bevel, the component guides itself home. Furthermore, in material handling, beveled edges on conveyor belts or chutes prevent items from catching or snagging, ensuring a smooth, uninterrupted flow from point A to point B. It’s a simple modification that prevents jams, reduces wear, and keeps production lines moving.

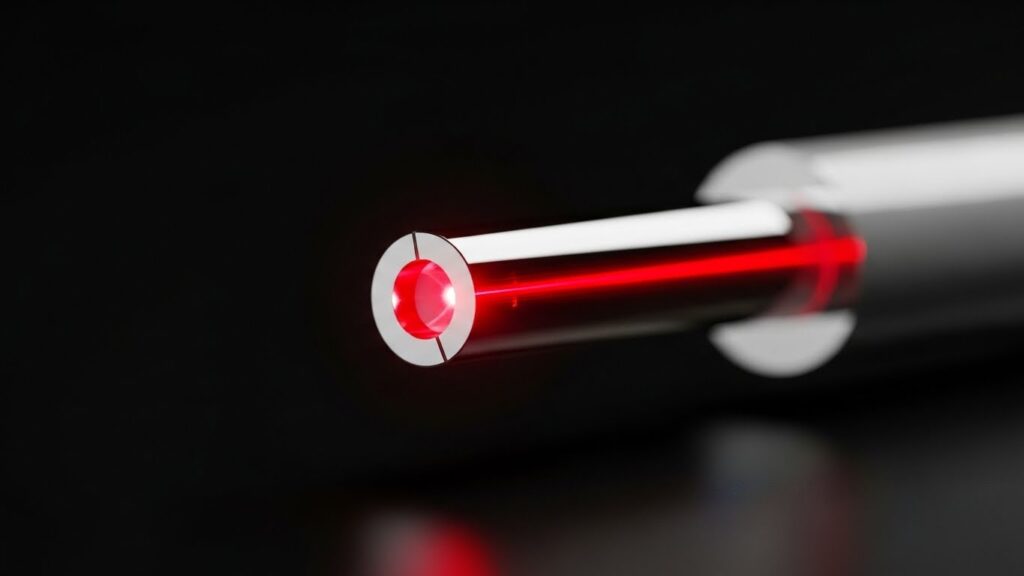

The Invisible Flow: Energy, Light, and Sound

Movement isn’t always physical. Beveled ends also masterfully direct the flow of energy, light, and sound. In optics, the beveled edge of a lens or a fiber optic cable is crucial for minimizing reflective loss. An angled cut, often polished to perfection, allows light to pass through the interface cleanly rather than scattering or bouncing back, ensuring signal strength and clarity in your internet connection or medical endoscope.

Acoustically, beveled edges and diffusers break up standing sound waves in recording studios and concert halls, preventing echoes and creating a more balanced auditory environment. Even in the realm of aerodynamics and hydrodynamics, the beveled leading edge of a wing or a ship’s hull is fundamental. It parts the fluid medium (air or water) efficiently, reducing drag and turbulence to facilitate smoother, faster movement. Here, the bevel manages the flow of invisible forces.

Aesthetic Movement: The Dynamic Line in Visual Design

Beyond pure function, the beveled end carries powerful aesthetic weight. In graphic and product design, a beveled edge on a smartphone, a countertop, or a logo creates a play of light and shadow that suggests thinness, precision, and dynamism. That sliver of angled surface catches the light differently, drawing the eye along its length and implying direction.

This creates visual movement on a static object. A square logo feels solid and grounded; the same logo with beveled corners feels active, approachable, and modern. In typography, subtle beveling on letterforms (often called “inking” in font design) can give the impression of dimension and direction, guiding the reader’s eye across the page. The bevel introduces a sense of depth and trajectory, making objects appear not as inert blocks, but as elements caught in a moment of transition.

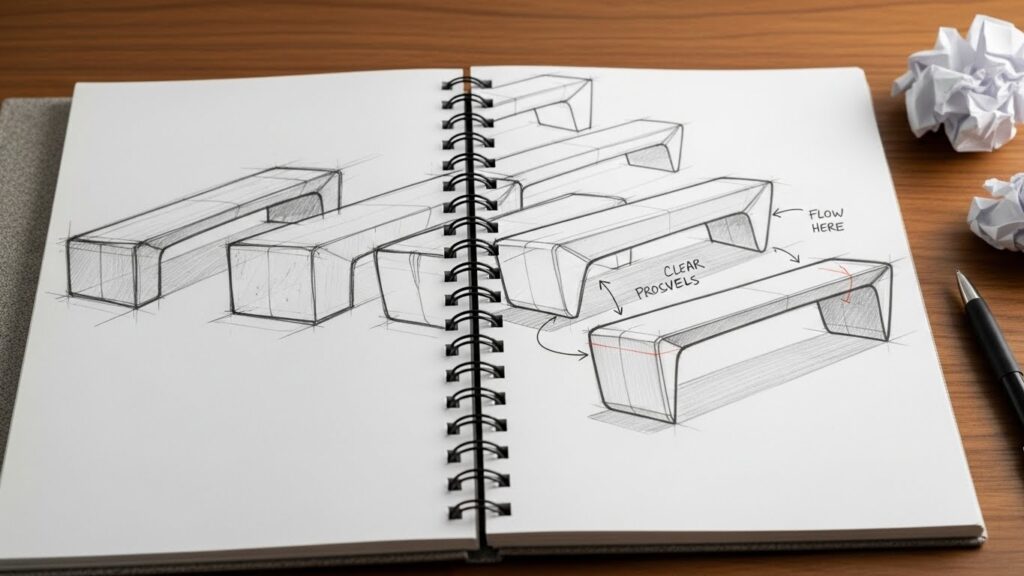

Implementing Beveled Ends: A Design Consideration

Understanding the “why” leads to the “how.” When should you consider a beveled end in your own projects? Ask these questions: Is there a transition point that feels abrupt or resistant? Could a user, object, or fluid flow benefit from a guided entry or exit? Is there a risk of damage, snagging, or injury from a sharp corner? Does the design feel visually static and need a hint of direction?

The bevel is a versatile tool. Its angle can be aggressive (a steep chamfer for heavy mechanical guidance) or gentle (a soft eased edge for tactile comfort). The key is intentionality. It’s not just about “softening an edge”; it’s about designing for a journey, however small. Whether you’re modeling a 3D printed part, sketching a furniture piece, or planning a garden path, remember that the end of any form is a point of interaction. How do you want that interaction to feel?

Conclusion: The Elegance of the Inclined Plane

The beveled end is a humble testament to the genius of the inclined plane—one of humanity’s oldest simple machines. It is a fundamental gesture in the designer’s toolkit, transforming barriers into pathways and obstacles into opportunities for smooth transition. From the monumental to the microscopic, these angled tips choreograph movement in all its forms: the movement of bodies through space, of parts into assembly, of light through cables, and of the eye across a form.

So, the next time you effortlessly roll your luggage off a curb, feel your keyboard comfortably under your wrists, or admire the sleek profile of a modern device, take a moment to appreciate the bevel. It’s a quiet, intelligent design decision that, quite literally, makes the world move more smoothly.