Internal Edge Texture: Hidden Perimeter Variation

In the world of design, engineering, and manufacturing, we often focus on the obvious: the sleek curves of a car’s body, the crisp lines of a smartphone, or the smooth finish of a countertop. Yet, lurking just beneath the surface of our visual and tactile experience is a subtle, powerful, and frequently overlooked characteristic: internal edge texture. This isn’t about the primary surface you see or touch first. It’s about the intricate landscape of the perimeter of internal features—the walls of a drilled hole, the channels of a fluid passage, the mating surfaces inside an assembly. Understanding this hidden variation is the key to unlocking higher performance, durability, and quality in everything from medical implants to aerospace components.

What Exactly is Internal Edge Texture?

Let’s define our terms. Edge texture refers to the surface irregularities along the boundary of a feature. When we talk about internal edge texture, we are specifically referring to these irregularities on the perimeters of features that are enclosed or recessed within a part. Think of the inside of a fuel injector nozzle, the threads of a screw, or the interior lumen of a catheter.

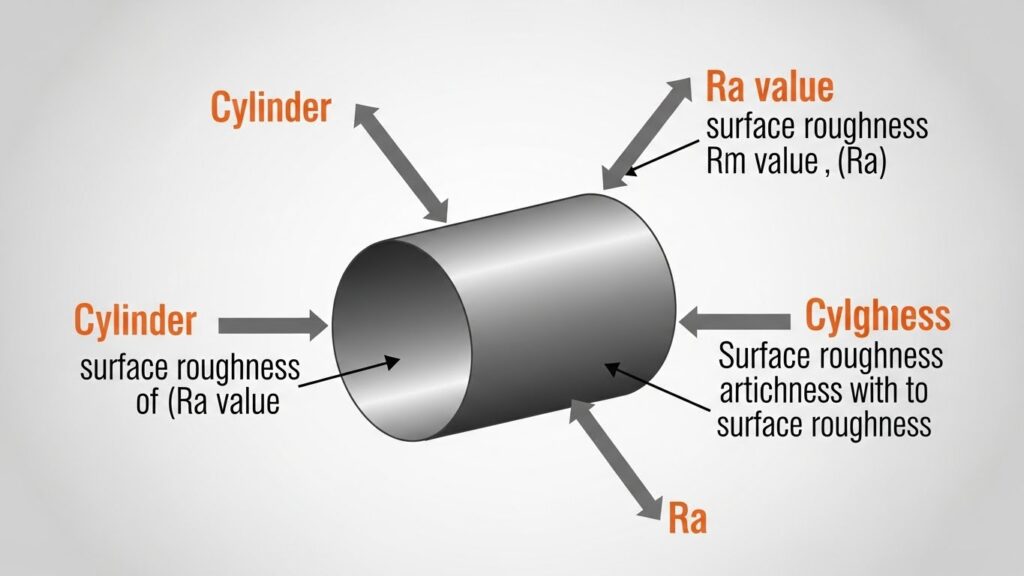

This texture is quantified by parameters like Ra (Roughness Average) and Rz (Maximum Height of the Profile), but its impact goes far beyond a number on a spec sheet. It is a “hidden” variation because it is often difficult to measure without specialized tools, easy to neglect during design, and yet it profoundly influences how a part interacts with its environment. A smooth external surface might win aesthetic approval, but the character of the internal edges often determines functional success or failure.

Why Internal Edge Texture Matters: The Functional Imperative

Ignoring internal edge texture is like building a race car with a polished exterior and a dirty, poorly tuned engine. The hidden perimeter variation dictates critical functional outcomes.

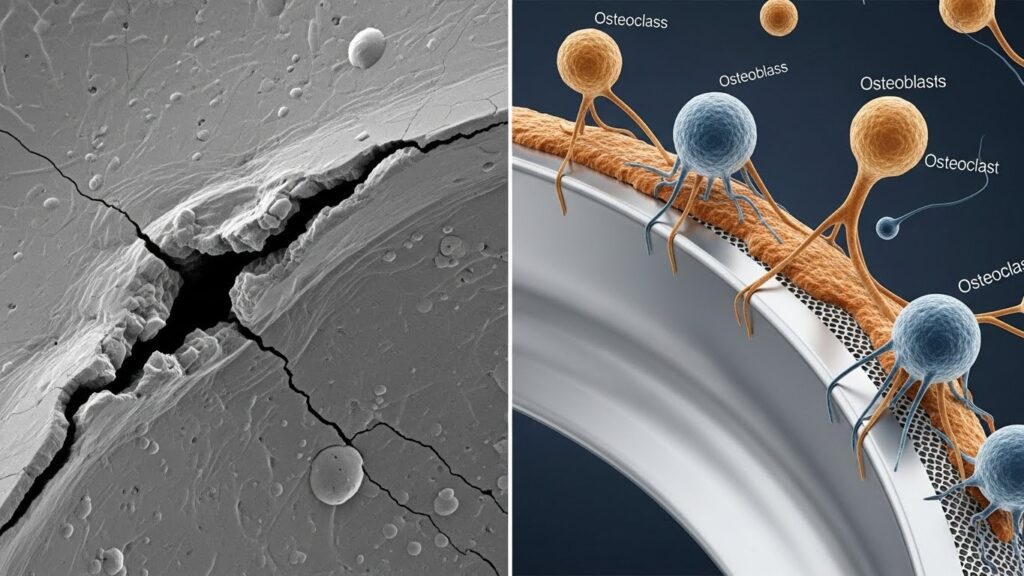

Fatigue and Fracture Resistance: Internal edges are prime initiation sites for cracks. A rough, machined texture with micro-notches creates stress concentrators. Under cyclic loading—like in a turbine blade or a bone screw—cracks can start here and propagate, leading to catastrophic failure. A controlled, smooth internal edge texture dramatically extends a component’s fatigue life.

Fluid Dynamics and Flow: In any system dealing with liquids or gases, internal edge texture is paramount. The roughness of a pipe’s interior wall creates friction, affecting pressure drop and flow rate. In high-precision applications like inkjet printer heads or pharmaceutical dispensing systems, an inconsistent internal texture can cause turbulence, cavitation, or uneven flow, ruining performance.

Sealing and Adhesion: When two parts mate or a seal is pressed against an internal shoulder, the texture of that contact zone is everything. Too rough, and you can’t achieve a proper seal; too smooth, and adhesives or gaskets might not grip effectively. The optimal internal edge texture ensures leak-proof connections and strong, durable bonds.

Biological Response: In medical devices, the body’s cells respond directly to surface texture. A bone implant with a strategically roughened internal texture (for screw threads or porous structures) promotes osseointegration—bone growth into the implant. Conversely, the interior of a vascular stent needs an exceptionally smooth finish to prevent platelet adhesion and clotting.

The Manufacturing Challenge: Controlling the Unseen

Creating consistent internal edge texture is one of manufacturing’s most sophisticated challenges. Unlike an external face, internal perimeters are often difficult to access for both tooling and measurement.

Tooling and Technique: The method used to create an internal feature inherently dictates its texture. A drilled hole will have a different texture than a reamed, bored, or electrical discharge machined (EDM) hole. Factors like tool wear, cutting speed, feed rate, and vibration all leave their unique signature on the internal edge. A worn drill bit doesn’t just make a slightly bigger hole; it creates a much rougher, more torn internal wall.

Post-Processing Access: How do you polish or treat a surface you can’t easily see or touch? Processes like abrasive flow machining (where a viscous media is forced through internal passages) or electropolishing (which uses electrochemical removal) are specifically designed to address internal edge texture. However, they add cost and complexity, making design-stage specification crucial.

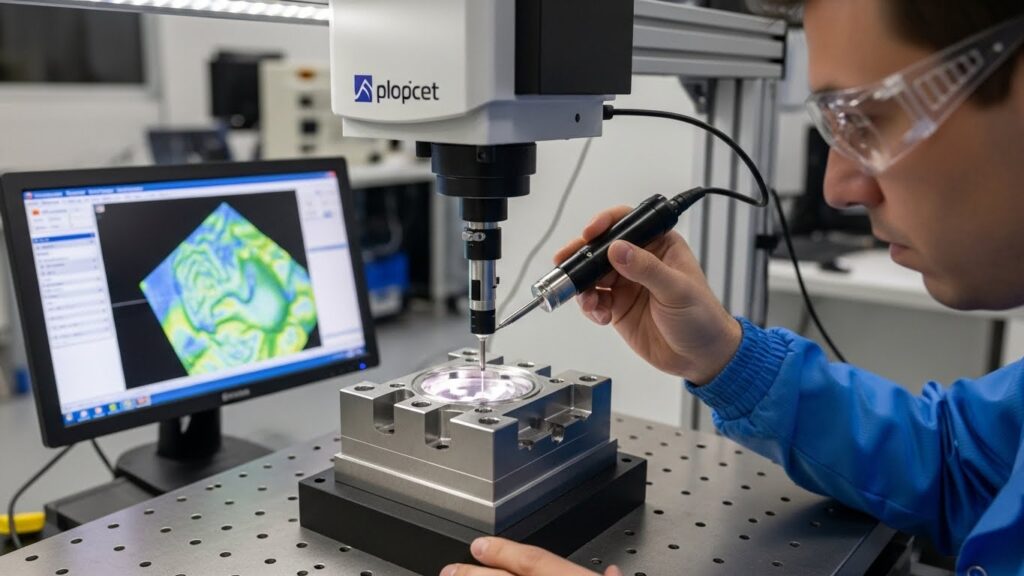

Measurement and Verification: This is the grand hurdle. You can’t run a standard profilometer across the inside of a tiny hole. Technologies like non-contact 3D optical profilometers with specialized lenses, focus variation microscopy, or even destructive cross-sectioning are required. This “inspection barrier” is why internal edge texture is sometimes relegated to an afterthought.

Designing with Internal Edge Texture in Mind

The key to harnessing this hidden variable is to design for it from the outset. This requires a shift from merely specifying a hole’s diameter to defining the required texture of its perimeter.

1. Functional Specification: On engineering drawings and CAD models, call out internal edge texture requirements explicitly. Use standard surface finish symbols with clear Ra/Rz values, and point the leader line to the internal edge in question. Distinguish it from the general surface finish note.

2. Process Selection: Choose your manufacturing and finishing processes based on the texture goal. Design features that are accessible for the necessary post-processing. For example, avoid designing deep, small-diameter blind holes if a smooth finish is required, as polishing them may be impossible.

3. Tolerancing for Function: Apply realistic tolerances. Demanding a mirror finish (Ra 0.1 µm) on an internal channel may be overkill and exponentially increase cost. Work with manufacturing engineers to define the functional roughness needed for the part to work reliably.

4. Prototype and Measure: Never assume the internal texture is correct. Build prototype samples and invest in the metrology to verify the internal edge condition matches the design intent. This data is gold for refining the process.

The Hidden Advantage: Turning Variation into Value

Mastering internal edge texture isn’t just about solving problems; it’s about creating opportunities. Companies that control this hidden perimeter variation gain a significant competitive edge.

They produce more reliable products with longer lifespans and fewer field failures. They enable miniaturization, as in micro-fluidics, where smooth internal channels are non-negotiable. They achieve higher efficiency in systems from hydraulic pumps to jet engines by minimizing parasitic friction losses. Ultimately, they move from merely making parts to engineering functionally optimized systems where every surface, seen or unseen, is designed with intent.

The internal edge is the final frontier of surface engineering. In the pursuit of perfection, looking beyond the obvious exterior and focusing on the hidden texture within is what separates good engineering from great engineering. By bringing this hidden variation to light, we build a foundation for innovation that is, quite literally, deeper and stronger.