Micro Surface Texture: Subtle Overall Variation

In a world saturated with visual stimuli, our deepest connections with objects are often forged through touch and subconscious perception. We reach for the matte finish on a smartphone, run our fingers along a softly textured wall, or appreciate the consistent, grain-like feel of a high-end tool. This is the silent, powerful domain of micro surface texture and its defining characteristic: subtle overall variation. Far from being random roughness, it is a meticulously crafted landscape of minute peaks and valleys, a deliberate pattern applied across a surface to achieve specific aesthetic, functional, and experiential goals. This blog post delves into the science, art, and application of this crucial but often overlooked design element.

What is Micro Surface Texture? Defining Subtle Overall Variation

Micro surface texture refers to the small-scale, three-dimensional topography of a surface, typically measured in microns (one-thousandth of a millimeter). When we specify subtle overall variation, we are describing a texture that is consistent across the entire surface but is not perfectly uniform or mechanical. Unlike a glossy, mirror-like polish (minimal variation) or a deep, aggressive knurl (high variation), a subtle texture possesses a gentle, controlled randomness.

Think of it like the skin of an orange versus a glass pane. The glass is smooth and specular. The orange peel has a defined, repeating pattern. Now, imagine a fine leather journal cover or a brushed metal surface. These exhibit subtle overall variation: there is a clear textural character, but your eye and hand perceive it as a cohesive, integrated whole, not a collection of distinct features. This variation reduces harsh specular reflections, hides minor fingerprints and scratches, and creates a soft, diffuse light interaction that is inherently pleasing.

Why It Matters: The Functional and Aesthetic Imperative

The application of micro texture is a decision that bridges engineering and sensory design. Its importance cannot be overstated for several key reasons.

Enhanced Grip and Ergonomics: A perfectly smooth surface can be slippery. Introducing micro-scale texture increases the coefficient of friction, providing a secure grip. This is critical for tool handles, surgical instruments, steering wheels, and consumer electronics. The subtlety ensures comfort during prolonged contact, unlike abrasive textures that can cause discomfort.

Light Management and Aesthetics: Micro textures scatter light diffusely. This eliminates distracting glare and hot spots, creating a soft, matte, or satin appearance that is perceived as premium and sophisticated. It allows color to appear deeper and more consistent from all viewing angles. This principle is used extensively in automotive interiors, luxury appliances, and architectural panels to reduce visual fatigue and enhance perceived quality.

Durability and Hiding Wear: A surface with subtle variation is inherently more forgiving than a pristine, polished one. Micro-scratches, dust, and fingerprints become far less visible because they get lost in the existing texture pattern. This maintains the product’s “like-new” appearance throughout its lifecycle, a major consideration for high-touch consumer goods and public-facing architectural elements.

Tactile Experience and Emotional Connection: Touch is an emotional sense. A pleasant micro texture invites interaction and conveys qualities like warmth, solidity, or precision. The gentle feedback from a textured button or the consistent feel of a device casing creates a subconscious dialogue of quality and intentionality with the user.

Creating the Imperceptible: Manufacturing Techniques for Micro Texture

Achieving controlled, subtle overall variation requires precise manufacturing techniques. The chosen method depends on the base material, desired scale, and production volume.

Chemical Etching: Using controlled chemical baths, this process can selectively remove material to create uniform matte finishes or specific micro-patterns on metals, glass, and some polymers. It’s excellent for complex geometries and achieving highly consistent, isotropic textures (uniform in all directions).

Abrasive Blasting (Bead/Media Blasting): Propelling fine media (glass beads, aluminum oxide) at a surface creates a stochastic, peened texture. By carefully controlling media size, pressure, and angle, manufacturers can produce a range of subtle satin finishes, from very fine to moderately coarse. This is a common method for metals and glass.

Brushing and Linishing: Mechanical abrasion with abrasive brushes or belts creates a directional texture, evident in classic “brushed aluminum” finishes. The overall variation comes from the natural inconsistency of the abrasive process, creating a pattern of fine, parallel scratches that scatter light.

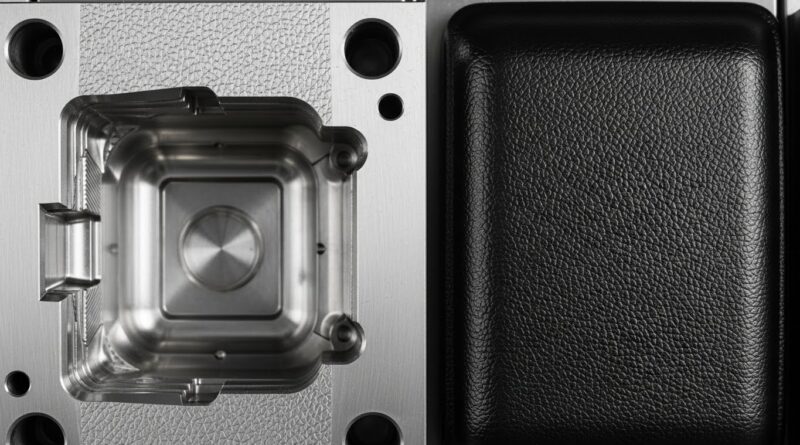

Patterned Tooling (Molds & Rolls): For mass-produced plastic and metal parts, the texture is often engineered directly into the mold, die, or rolling mill. Using techniques like photochemical etching or laser engraving on the tool steel, a micro texture is transferred to every part. This is the most cost-effective method for high-volume production and ensures part-to-part consistency.

Advanced Additive Manufacturing: 3D printing technologies, particularly those with fine resolution like SLA or MJF, can directly print micro-textured surfaces. The layer lines themselves can be considered a texture, but specific patterns can also be digitally designed into the surface model for functional purposes like increased surface area for bonding or specific fluid dynamics.

Beyond Industry: Micro Texture in Architecture and Nature

The principle of subtle overall variation is not confined to product design. It is a fundamental element in architecture and omnipresent in the natural world, teaching us valuable lessons.

In architecture, textured concrete (board-formed or lightly sandblasted), wire-brushed wood, hammered metal panels, and rough-cast glass all utilize micro texture to manage light, create scale, and evoke emotion. A textured wall surface changes appearance with the sun’s angle, creating a dynamic, living facade. It adds a human scale to large structures and provides visual interest without overwhelming ornamentation.

Nature is the ultimate master of functional micro texture. The lotus leaf’s self-cleaning ability stems from its hierarchical micro and nano-texture. Shark skin reduces drag through microscopic riblets. Moth eyes have anti-reflective nanostructures. Even the pleasing feel of a rose petal or a peach’s skin is a result of exquisitely evolved subtle surface variation. These biomimetic lessons are increasingly informing engineering solutions for durability, cleanliness, and efficiency.

Specifying and Measuring: The Language of Texture

To effectively implement micro texture, designers and engineers must speak a common language with manufacturers. This involves both qualitative and quantitative specification.

Qualitative Samples: Physical “texture masters” or “plaques” are the gold standard. These are sample panels with the exact desired finish, used for visual and tactile approval. They are often given designations like “MT-11040” (Matte Texture, code 11040).

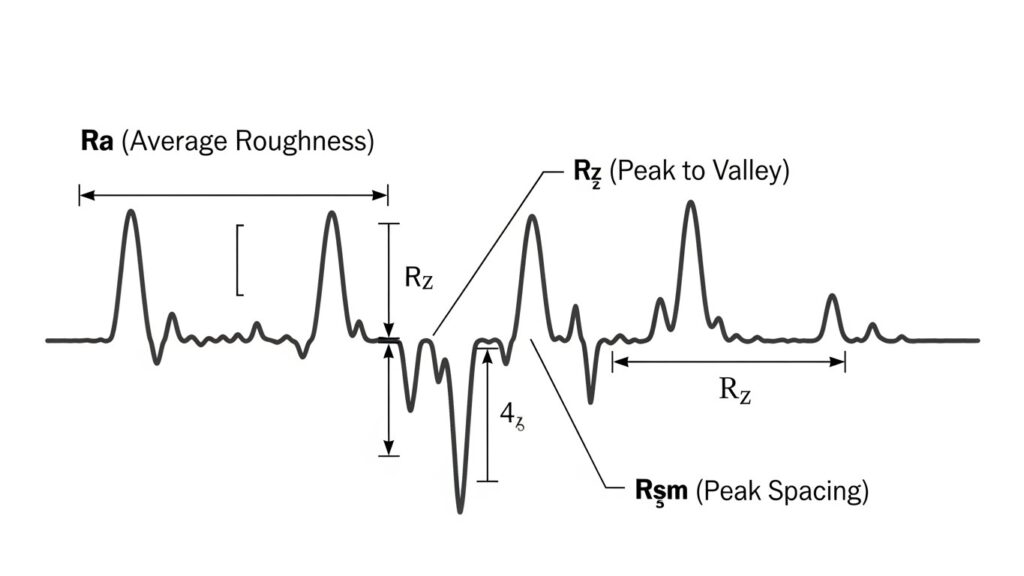

Quantitative Parameters (Surface Metrology): For critical applications, texture is measured using profilometers. Key parameters include:

Ra (Average Roughness): The arithmetic average of absolute distances from the mean line. A common descriptor (e.g., Ra 0.8µm).

Rz (Mean Peak-to-Valley Height): Averages the heights of the highest peaks and deepest valleys.

Rsm (Mean Spacing): The average distance between texture profile peaks. This helps define the “fineness” of the texture.

Specifying a combination of these values, along with a sample, ensures the subtle overall variation is reproduced accurately and consistently across production runs and between different suppliers.

The Future: Smart Surfaces and Dynamic Textures

The future of micro surface texture is moving from static to dynamic and functional. Research is advancing in areas like:

Functional Graded Textures: Surfaces where the texture varies across a part to meet local needs—smoother where it touches skin, grippier where held, and with specific patterns for thermal management or fluid flow in another area.

Responsive and Active Textures: Using materials like shape-memory polymers or alloys, surfaces that can change their micro texture in response to heat, electricity, or other stimuli. Imagine a grip that becomes more textured when your hands are sweaty or a aerodynamic surface that smoothens at high speed.

Nanotexture for Superfunctionality: Pushing into the nanometer scale to create surfaces with unprecedented properties: superhydrophobic (extremely water-repellent), anti-icing, bactericidal, or with tailored optical effects beyond simple matte diffusion.

In conclusion, micro surface texture with subtle overall variation is a fundamental pillar of good design. It is the intersection where measurable engineering meets subjective human perception. It is the detail that may not be consciously noticed but is always felt, building an unspoken narrative of quality, intention, and sophistication. By mastering this subtle language, designers, engineers, and architects can create products and spaces that are not only more functional and durable but also more resonant and human.